Jan 15, 2025

Does Schrödinger’s Cat Really Exist? Quantum Computers and the Multiverse

Ryunsu Sung

Quantum mechanics is a theory in physics that explains the motion of very small particles such as electrons and photons. This theory works in a way that is completely different from classical mechanics. In classical mechanics, the position and velocity of an object are determined precisely, whereas in quantum mechanics, the state of a particle can be described only in terms of probabilities.

The key tool for these probability calculations is the wave function.

What is a wave function?

A wave function is usually written as \(ψ(x,t)\), and it is a mathematical expression that contains all the information about a quantum system. Put simply, it acts like a map that shows the likelihood of where a particle might be. However, the function itself is not something that can be observed physically; it is merely a tool for calculation.

The square of the magnitude of the wave function, \(|ψ(x,t)|^2\), represents the probability density. For example, if you want to calculate the probability of finding a particle at a specific position x at a specific time t, you use this value. Using this function, you can also calculate not only position but other properties such as momentum and energy.

Hilbert space

The space in which the wave function is represented is not physical space. Instead, it is defined in an abstract mathematical space called Hilbert space. This space serves as a kind of stage on which quantum states are represented as vectors.

- What is Hilbert space? Simply put, it is a multidimensional space in which all possible quantum states can be represented mathematically. In this space, a wave function is expressed as a single vector, and through this vector one can calculate various properties of the system.

- In Hilbert space, operators such as position and momentum are used to obtain measurable physical quantities.

Thanks to this abstract space, the mathematical structure of quantum mechanics becomes possible, but Hilbert space does not exist as a space in the real world. When we make an observation in quantum mechanics, we say that the wave function "collapses" into a specific state (wave function collapse), which means that the particle’s position is determined definitively.

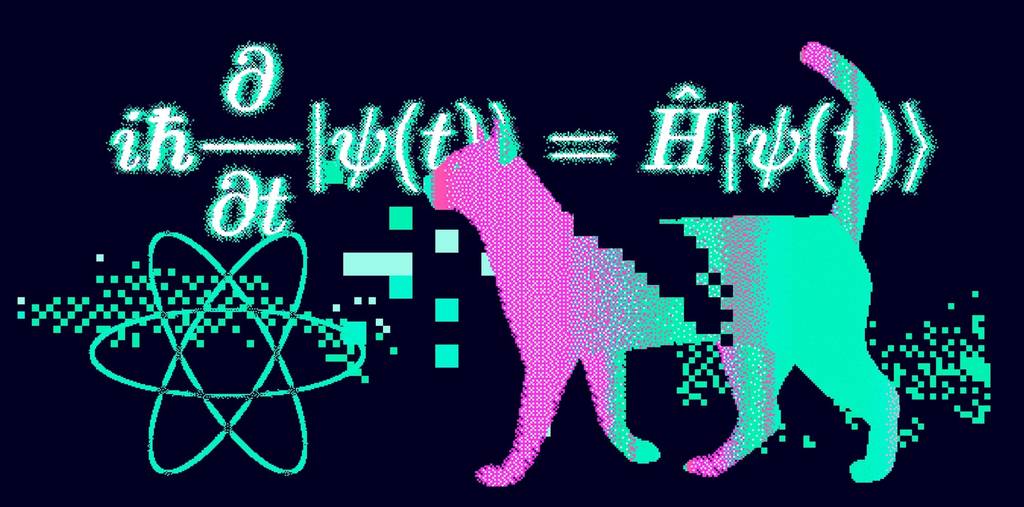

In other words, when we open a box that contains a cat and a vial of poison that kills the cat with a 50% probability, we can only ever observe the cat as either alive (1) or dead (0). Before we open the box and observe the cat, the cat is said to be in a quantum superposition state of being both alive and dead at the same time (1+0) (\(|ψ〉=α|φ〉+β|ξ〉)\). This superposition exists only as a theoretical construct in quantum physics; it has never been observed in reality, and it is effectively safe to assume that it will never be observed.

This famous thought experiment, known as Schrödinger’s cat, was in fact devised by physicist Erwin Schrödinger to highlight just how counterintuitive and absurd the concept of a "quantum superposition" really is. This perspective is considered to follow the Copenhagen interpretation. The Copenhagen interpretation is one of several interpretations of quantum mechanics and is known as the orthodox view associated with Niels Bohr and Werner Heisenberg, among others.

The multiverse and quantum computing

The Copenhagen interpretation provides a mathematical account of the wave function, but it is criticized for failing to offer a concrete explanation of the underlying phenomenon of quantum superposition. The wave function is accurate enough to be used in modern semiconductor circuit design, yet when a "collapse" occurs (when an observation is made) and only one outcome appears according to probability, the Schrödinger’s cat problem emerges. If, upon opening the box, the cat is alive, then where, exactly, is the other 50% probability—the dead cat?

The many-worlds interpretation was proposed as an answer to this question. The many-worlds interpretation argues that multiple universes—a multiverse—exist. According to this view, when we open the box, the quantum superposition does not collapse into a single outcome determined by probability. Instead, the universe in which the cat is alive is the one we inhabit, while the universe in which the cat is dead exists separately.

Researchers developing quantum computers tend to favor the many-worlds interpretation, because the way quantum computing operates aligns naturally with it. According to their argument, a quantum computer uses quantum entanglement and quantum superposition to enable parallel computation across the multiverse.

Quantum entanglement

Quantum entanglement is a phenomenon in which two particles that are physically far apart remain strongly connected, so that the state of one particle instantly affects the state of the other. Particles in an entangled state share their states even when they are physically separated. For example, once you measure the state of one particle, you immediately know the state of the other.

This directly contradicts classical physics, because if two particles can influence each other instantaneously over an enormous distance, it implies communication faster than the speed of light.

According to the many-worlds interpretation, the states of entangled particles branch like a vast "tree of universes" that contains all possible outcomes. Each measurement creates a new universe, and every possible result exists simultaneously in a different universe. Under this interpretation, quantum computers are seen as performing multiple calculations at once in parallel universes through entanglement.

The theoretical principles of quantum computing

- The role of quantum entanglement:

- Parallel computation from a many-worlds perspective:

- How it differs from the Copenhagen interpretation:

The problem is application

Even if the multiverse really exists, it is impossible for us to observe it. We struggle to properly observe and understand even the universe we inhabit, so trying to find definitive evidence that other universes exist is a foolish idea. Yet there is of course no proof that they do not exist either, which is why physicists who follow the Copenhagen interpretation and those who follow the many-worlds interpretation continue to clash over this.

Einstein rejected the idea that quantum phenomena—or more precisely, the foundations that underlie them—are fundamentally probabilistic. He posed the famous question, “If no one is looking at the moon, does the moon still exist?” to argue that quantum mechanics, too, must obey causality (cause and effect), and insisted that “God does not play dice.” Later, evidence for the existence of quanta was found in the double-slit experiment, and Einstein ultimately turned out to be wrong. But I would still like to ask: “If no one can ever observe something, can it truly be said to exist?”

Because of our limitations as observers, it is impossible to prove quantum mechanics and its interpretations in the real world, rather than in abstract mathematical constructs such as the Hilbert space mentioned earlier. Even if, as Einstein argued, there is some underlying mechanism that truly governs quantum mechanics, the probability is very high that it will be impossible for humans to understand and apply it.

Newsletter

Be the first to get news about original content, newsletters, and special events.