Apr 05, 2024

Effective Altruism and the Limits of Economics

Ryunsu Sung

To quote Wikipedia, effective altruism (效果的利他主義, English: effective altruism) is “a social movement or ethical trend that seeks to realize altruism based on sound evidence and reasoning. It differs from traditional altruism and charitable work in its approach, in that it tries to analyze, in a systematic and consequentialist way, which actions most efficiently affect others and humanity.”

A leading proponent is the ethicist Peter Singer, whose core ideas are well articulated in his book The Life You Can Save.

It is also a popular philosophy in Silicon Valley, which leads the world in technology, culture, and ideas (even if the idea itself was not born there). Park Sang-hyun, publisher of Otter Letter, once described effective altruists in a JoongAng Ilbo column as follows: “Unlike traditional rich donors who give large sums to charity, they pursue, based on reason and evidence, the most efficient ways to help others and humanity.”

Effective altruism would say that if I had 10 million won in spare cash, instead of paying for a surgery that would save my next-door neighbor—someone I’ve known for a long time—with 100% certainty, I should invest that money in developing a treatment that has a 1% chance of saving 10,000 patients with incurable diseases. If you calculate the return on investment for society as a whole (in expected value terms), the utility of saving the one neighbor is 10 million won, whereas the treatment is worth 1 billion won (10 million won × 10,000 / 100).

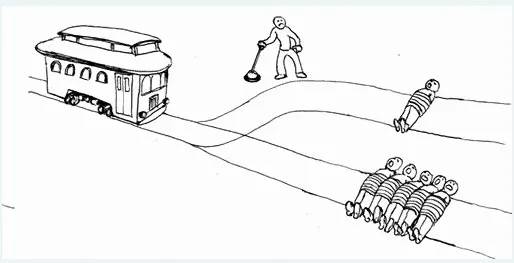

Because it makes claims like this, effective altruism is inevitably closely tied to ethics, specifically to utilitarianism. A classic example associated with utilitarianism—often summarized by the phrase “the greatest happiness of the greatest number”—is the trolley dilemma. The trolley dilemma is a thought experiment that asks whether you would pull a switch to divert a moving train so that it kills only one person, or leave it as is and allow five people to die.

In real life, the odds of facing a situation like the trolley dilemma are low, but when researchers run this kind of thought experiment, roughly 75% of people reportedly choose not to manipulate the switch to kill just one person. This is so even though, from a utilitarian perspective, the socially optimal choice in terms of outcomes is to pull the switch and sacrifice one to save five.

We should pay attention to the fact that utilitarianism is a philosophical stance, but people’s actual behavior often does not follow it. The utilitarian approach focuses on humans as members of society and argues that, for the survival and flourishing of the group as a whole, individuals should consider the consequences their actions will have on others.

This consequentialist approach (where actions are justified by their outcomes) contrasts with a deontological approach (where actions are justified by a set of rules). For example, in the film Do the Right Thing, the director shows us the socially problematic actions of the protagonists and their consequences—death and destruction—without sugarcoating them. Yet by lending us the characters’ lens, he makes us empathize with the motives that led them to make those choices, even though the outcomes were clearly wrong.

Of course, a psychopath would not consume the film in the way the director intended. But the fact that Do the Right Thing received critical acclaim at Cannes and elsewhere, and was selected by the U.S. Library of Congress for preservation as a film that is “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant,” can be seen as indirect evidence that humans instinctively prefer a deontological approach (for example: college admissions procedures should be fair).

Results from the ultimatum game, a staple of behavioral economics and game theory, also support this. In the ultimatum game, there is one proposer and one responder. The proposer receives 100,000 won from the experimenter and decides how to split it between themselves and the responder. If the responder accepts the proposed split, the two subjects each receive the amount offered. According to Nash equilibrium, the responder should accept any positive amount, because they are still better off than with nothing. In reality, however, when the proposer offers a clearly smaller share to the responder—say an 8:2 split—the responder is much more likely to reject it out of a sense that it is “too dirty and unfair,” even at a cost to themselves.

Sam Bankman-Fried (SBF), the founder of what was once the world’s second-largest crypto exchange, FTX, and now a convicted financial fraudster serving a 25-year sentence, is also one of the believers in effective altruism. Given that he is an MIT-educated elite, this is not particularly surprising. Many elites in the United States and the broader West tend to favor a consequentialist approach (college admissions are structured this way; top universities prefer applicants who, based on their past record, are most likely to contribute to the school’s future, and practices like donor admissions or legacy admission are part of this). They seem to believe that if they can just become billionaires as quickly as possible, they can then reallocate resources to wherever will benefit society the most. Following this logic, SBF founded the quantitative crypto trading firm Alameda Research and then FTX, and appears to have used customer funds held in custody as a leverage source for Alameda Research or made decisions that personally benefited him (which, as it happens, were also illegal).

Here is where the limits of effective altruism become apparent: it can be used to justify decisions that benefit oneself but may harm others on the grounds that, in the end, they are socially beneficial. Of course, most people are somewhat self-interested and have a tendency to rationalize their behavior, so we cannot say that such decisions are 100% wrong in every case. But if elites—people with outsized social influence—routinely violate social norms, moral standards, and the law, all in the name of effective altruism, we do not need much imagination to picture what that society would look like.

The utilitarianism that underpins effective altruism ultimately rests on economics. Economics is a discipline focused on extracting the maximum possible utility from limited resources (which is why it is full of equations and gives me a hard time), so ideologically the two are similar.

This is precisely the problem with classical economics and with effective altruism. From a utilitarian or consequentialist worldview, they overlook something essential about people. In effective altruism, there is no real place for the individual or for empathy. And I would argue that this is also why economics so often fails.

Newsletter

Be the first to get news about original content, newsletters, and special events.