May 02, 2022

When the Stock Market Crashed, This Is What Warren Buffett Bought

Ryunsu Sung

For weeks now, pollen has been swirling in the air and tormenting me and my hay fever. As the reaction to the pollen kept building and eventually turned into pharyngitis, I finally threw in the towel and went to an ENT clinic to get antibiotics and anti‑inflammatory painkillers. I had already been taking antihistamines every day, but that alone just wasn’t enough.

The stock market is also showing a persistent allergic reaction to war and monetary tightening. The problem is that the market has neither antihistamines nor anti‑inflammatory painkillers. There is no sign the war will end, and inflation refuses to cool down.

Jerome Powell and the Fed governors, who had looked as dovish as gentle lambs, are now threatening that they could raise the policy rate by 75 bps. Tech companies that benefited handsomely from the pandemic‑era shift to remote life are now suffering crashes because of slowing growth and rising rates. When will this pollen finally stop?

ARKK, the flagship ETF run by Ark Investment Management’s “money tree” Cathie Wood, is down 50% year‑to‑date. If you had invested 100 million won at the start of the year, you’d have roughly 50 million left. And if you factor in the emotional scars and stress, your loss is even bigger.

“Sell in May”

— so the saying goes. It’s a Wall Street adage that because stock returns over the summer tend to be weak on average, you should sell in May and come back in October. If we take that literally, it implies an even gloomier future than the already dreadful returns from last October through this April.

The Dow Jones Industrial Average is already posting the third‑worst year‑to‑date decline since 1928. The Nasdaq’s April performance is its worst monthly drop since 2000.

This is clearly visible in AWARE’s weekly tracker of the four major indices. The small‑ and mid‑cap‑heavy Russell 2000 is in the lead with a decline of 3.91%, while the Nasdaq, which had been “leading from behind” for several weeks, is close on its heels at 3.73%. Only the Dow Jones Industrial Average is showing a relatively “stable” drop of 2.54%.

The joy of Thursday’s rebound was short‑lived; on Friday the stock market greeted investors with an even harsher tone.

So should we follow the “Sell in May” adage, dump our already‑halved stocks, and hope to come back in October?

Not necessarily. People like to say our ancestors’ proverbs are never wrong, but in reality we tend to remember only the sayings that happened to be right among the countless ones that were wrong. It is true that average returns from May to October, at 2%, have historically been lower than the 5% average from November to April. But if you stop investing in May, you miss out on the power of compounding.

Of course, you might push back and say, “Are you telling me to enjoy compounding in the negative in a falling market?” But in the last week of April, we started to see a slight change in the pattern.

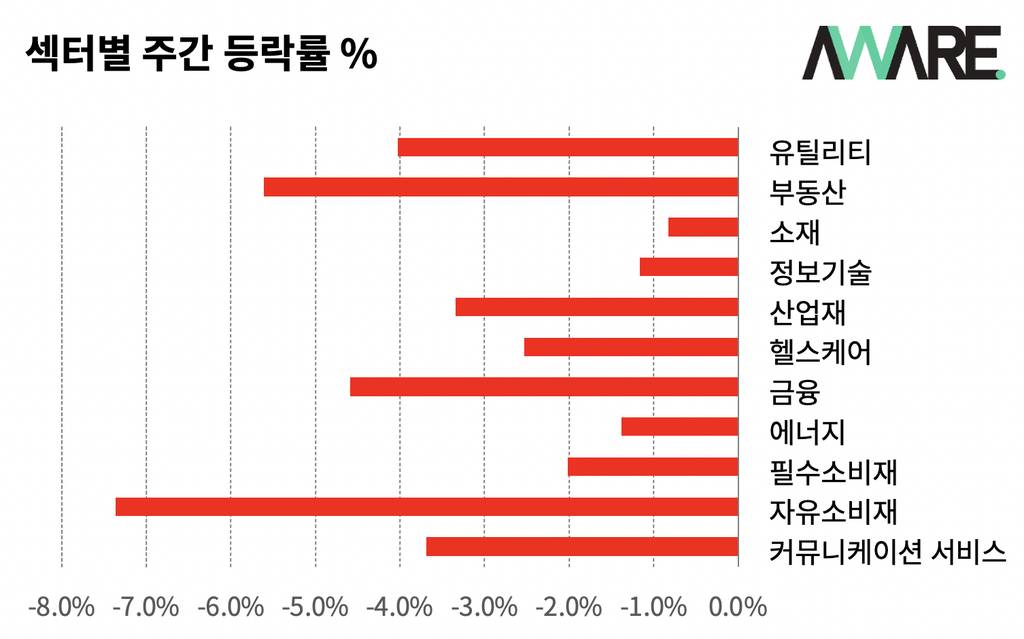

Looking at weekly sector performance (a sea of red), we see that information technology, which had led the decline for several weeks, actually posted the second‑best performance at −1.16%. In contrast, consumer discretionary (−7.36%) and financials (−4.59%) suffered particularly steep drops.

Consumer discretionary was likely dragged down heavily by Amazon’s (AMZN) 14% plunge. Automakers and auto‑parts companies, which have been struggling recently due to the semiconductor shortage, are also classified as consumer discretionary. Amazon’s 3.8 billion dollar net loss in the first quarter was largely due to a 7.6 billion dollar mark‑to‑market loss on its 18% stake in Rivian Automotive (RIVN) as Rivian’s share price collapsed.

Financials have continued to slide despite rising Treasury yields, contrary to market expectations. That reflects a perception that the outlook for the economy is quite negative. While the 10‑year yield is stabilizing around 2.9%, the 2‑year has surged into the 2.7% range. You can probably see how this shatters the usual bank‑stock thesis of expanding net interest margins.

“So does that mean there’s nothing left to invest in?”

Let’s think this through again. The two biggest problems in today’s economy are the Russia‑Ukraine war and the Fed’s aggressive tightening policy. The war is ongoing, and the Fed’s aggressive tightening is, so far, mostly just talk.

It is a given that the Fed will raise rates by 50 bps in May, but I’m not convinced we can say the same about the year‑end policy‑rate band of 3–3.25% that derivatives markets currently see as likely. Until late last year, the Fed was parroting the same line over and over:

“Inflation is a transitory phenomenon and will gradually come down over the next several months.”

It’s a bit like a drug or supplement maker dismissing side effects by saying, “That’s just a healing crisis.” Modern medicine doesn’t recognize that concept. Even the ultra‑elite Fed could not have predicted that inflation would persist this long or that the Russia‑Ukraine war would break out. The fact is that over the past two years, the Fed’s inflation forecasts have been no better than a monkey flipping a coin.

The silver lining is that the Nasdaq’s five‑year uptrend, despite the recent crash, now looks somewhat more reasonable. I say “somewhat” because even the flattest red trend line is drawn through two prior peaks and the current peak. That makes it more reasonable, but not exactly cheap.

From its 52‑week high around 16,000, the index is down about 20%, which has been enough to quiet some of the constant talk about a stock‑market bubble. Netflix (NFLX), once a member of the FAANG group of major U.S. growth stocks, has fallen 72% from its peak, shrinking from a market cap of over 200 billion dollars to around 84 billion—essentially cut to a third. Both Big Tech and Small Tech have contributed to the index’s decline.

By contrast, Microsoft (MSFT), which reported solid earnings, is down only about 17% from its high and is holding up better than the index. This isn’t indiscriminate selling; the biggest damage has been inflicted on companies whose future value was priced in most aggressively. When a lot of future value is priced in, you’re also taking on a lot of future uncertainty.

So let’s go back to the supposed root causes: war and inflation.

1. War: No one knows when it will end. But…

When the war first broke out, most military experts predicted that Russia would take Kyiv in a matter of days or weeks. Thanks to massive military and resource support from the U.S. and Europe, however, Ukraine succeeded in defending its capital. It was then widely assumed that Russia, shifting its focus from the north and west to the eastern Donbas and the south, would seize those regions and secure access to Ukraine’s ports.

Yet the BBC map above looks almost identical to the one from a month ago. Russian forces, which had been rapidly taking control of the southeast, have made virtually no meaningful gains over the past month.

Russia, however, is unlikely to have the capacity to endure a long, grinding war. We’re already hearing that even people close to Putin are growing weary.

The ruble, which had plunged, appears on the surface to have recovered its previous value, but the Bank of Russia’s policy rate is currently 14% (down from 17%), making it hard to borrow money in an already weak economy. To make matters worse, by demanding payment for Russian resources in rubles, Moscow has effectively cut off the foreign‑currency earnings that could have been useful if sanctions were ever lifted. For reference, the policy rate in the Czech Republic—often cited as a poor country in Eastern Europe—is currently only 5%.

Cracks emerge in Russian elite as tycoons start to bemoan invasion – The Washington Post

Putin may be purging elites who defy him, but Russia’s oligarchs ultimately built their fortunes on resource exports, so they are hardly thrilled about being cut off from the outside world. The Bank of Russia itself is forecasting that GDP will shrink by about 10% this year alone, which means a brutal winter is coming for ordinary Russians.

For comparison, South Korea’s GDP growth rate during the 1998 Asian financial crisis was −5.1%. When an economy stops growing, life gets hard for most people. Russia’s economic downturn is even steeper than during that crisis… 🤦♂️

2. Inflation: Will it just keep climbing?

The Federal Reserve is now openly rattling its saber about tackling inflation. For the record, I was one of the people sounding the alarm about “inflation” back in June 2020. The logic was simple: an enormous amount of money had been printed, and once that money started to circulate, inflation would be inevitable. I held that view through late 2021 and into early this year. Hard as it may be to believe now, “transitory inflation” was the consensus view in finance until the middle of last year. At the time I joked, “Our lives are transitory too.”

But something feels off. The same people who once treated transience as a virtue are now obsessing over persistent inflation. So I’m using Fed Chair Jerome Powell himself as a kind of human indicator and betting that this time inflation will subside earlier than the Fed expects. Call it a “reverse Powell trade.”

Kidding aside, there are two key variables behind my view that inflation will start to ease sooner (I’m talking about timing, not speed).

1. Lifting of lockdowns in major Chinese regions

Why would China’s lockdowns affect inflation? Because China effectively serves as the world’s factory. You might say that if Chinese factories shut down, we can just run Korean factories harder, but as you know, there is a very high probability that the raw materials and components our factories need are themselves made in China. A swift resumption of production at Chinese plants would go a long way toward easing supply‑chain bottlenecks.

2. “Stabilization” of oil prices

The single biggest driver keeping inflation elevated right now is energy prices. With crude oil in such short supply, substitute fuels like coal are also getting more expensive, and the prices of the many chemicals and fertilizers derived from oil are rising as well, feeding through into consumer goods and food prices.

Russian crude and natural gas are still flowing into the market, and no matter how much Putin blusters, it is hard to imagine Russia cutting off resource exports that account for the bulk of its national income.

“So what did Buffett buy?”

It wasn’t Warren Buffett personally, but Berkshire Hathaway (BRK), where Buffett serves as chairman, went on a buying spree in the first quarter and loaded up on Chevron (CVX). Chevron drills oil out of the ground, refines it, and sells it—a very anti‑environmental business. If companies like this didn’t exist, we wouldn’t be driving cars and tormenting the planet the way we do.

Vice chairman Charlie Munger has bluntly pushed back against negative views on oil, saying that crude will “remain useful for the next 200 years.” We should remember that no matter how much we ramp up renewables, we are still a long way from replacing oil demand. With WTI crude selling at around 100 dollars a barrel, oil companies are effectively drilling money out of the ground at a furious pace.

Newsletter

Be the first to get news about original content, newsletters, and special events.