Nov 09, 2022

Inside Powell’s Mind: What Past Rate Cuts Reveal

Sungwoo Bae

At the November 2 FOMC meeting, Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell commented on the pace of rate hikes.

He noted that, given the lag with which monetary policy affects the economy, the Fed could slow the pace of hikes, but he repeatedly emphasized his concern about inflation becoming entrenched.

He also said the level of the terminal rate could end up higher than previously expected,

signaling that rate hikes may proceed more slowly, but ultimately go further.

Since the end of the gold standard, the dollar has become the currency recognized by countries around the world.

And the Fed issues this dollar and pursues monetary policy aimed at maintaining the stability of the financial system.

Every word from the Fed is watched closely across the globe, and its decisions have a profound impact on the broader economy.

Right now, the Fed is raising rates at a very rapid pace,

and the fact that not only the Fed but central banks around the world are hiking rates simultaneously has drawn concern from the World Bank.

With rates rising relentlessly, anyone interested in investing has probably had this thought at least once:

“When on earth will rates finally shift to an easing stance?”

That is why we put this piece together.

Since August 15, 1971, when the gold standard was abolished and the dollar moved to the center of the global economy,

what were the circumstances each time Fed chairs cut rates, and what exactly did they say?

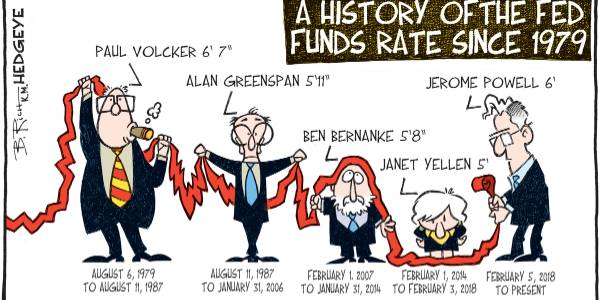

Alan Greenspan (1987.08.11 ~ 2006.01.31)

Alan Greenspan, a Republican, was the 13th Fed chair and holds the record for the longest tenure.

The economy under Greenspan was, in a word, outstanding. Growth was strong, the economy was expanding, and inflation was contained—a classic “Goldilocks economy.”

He believed that with low inflation and steady growth, monetary policy could be used to fine-tune the macroeconomy almost perfectly.

On June 5, 1989, following an FOMC conference call,

Chair Greenspan lowered the federal funds rate, which had been on a steady upward path, from 9.81% to 9.56%.

“There is clearly a puzzle as to why the wage behavior is as soft as it is, given the tightness of the labor markets.”

“It is clearly puzzling that wage behavior is this subdued, given how tight the labor market is.”

The key reason Greenspan judged that inflation pressures had eased that day was wage dynamics—the relationship between labor market tightness and wage growth.

He remarked that it was puzzling to see a tight labor market without corresponding wage pressures.

A tight labor market normally means demand for labor exceeds supply,

which pushes wages higher, feeds into inflation, and leads the Fed to feel compelled to raise rates.

But this time was different. The labor market was tight, yet wage behavior was not responding in kind.

This suggested that the inflation process was stabilizing rather than accelerating,

and Greenspan concluded that the risks of cutting rates were lower than the risks of keeping them where they were.

This marked the beginning of a series of rate cuts that continued until the policy rate reached 3.0% in 1992.

On July 6, 1995, following the July 5–6 FOMC meeting,

Greenspan cut the federal funds rate from 6% to 5.75%, reversing the hikes that had been implemented since 1992 to contain inflationary pressures.

Equity prices were rising, but growth was slowing, and the move was intended to address that slowdown.

“As I saw it, virtually all of us were concerned about asymmetric risks on the down side, but no one thought the probability of a recession was better than 50/50.”

“As I saw it, virtually all of us were worried about downside asymmetric risks, but no one said the probability of a recession was greater than 50%.”

Asymmetric risk refers to taking on risk in situations where the potential upside is much larger than the downside you are exposed to.

Imagine a shepherd comes to a trader and says he wants to sell his entire flock of 100 sheep.

The trader cannot clearly count whether there are exactly 100 sheep because the barn is dark,

but he does know that villagers will buy the sheep at twice the price he pays.

That is what asymmetric risk looks like.

Now suppose the trader hears a false rumor that the shepherd is in a hurry to get home and will therefore sell the sheep at a much lower price later.

If he believes that misinformation and waits for the price to fall instead of taking the asymmetric risk, he ends up missing a very attractive opportunity.

Greenspan pointed out that no one around the table had actually put a number on the probability of recession that day.

In other words, even if asymmetric downside risks were lurking, the likelihood of those risks being triggered was judged to be low.

He then argued that cutting rates was reasonable, citing the fact that “three weeks ago, every indicator we had suggested the economy was weakening.”

On that basis, he pushed for a rate cut.

Subsequently, the Fed went on to cut rates further, citing as key reasons the unemployment rate stuck at 5.6% year-on-year and retail sales coming in below expectations.

On September 29, 1998,

after a brief rise to 5.5% in March 1997, the policy rate was cut back down to 5%.

The 1998 rate cuts followed essentially the same logic as those in 1995.

They were, in effect, insurance against a worsening downturn.

On January 3, 2001, following an FOMC conference call,

the policy rate was cut from 6.5% to 6%.

Greenspan repeatedly voiced concerns about a deteriorating economy.

He said that economic growth was steadily slowing, unemployment was likely to rise sharply, and corporate earnings per share were falling rapidly.

He went on to say that conditions abroad were even worse than in the United States or Europe, and that those negative shocks would eventually spill back into the U.S. economy.

From 1995 to 2001 was the era of the dot-com bubble.

Greenspan paid close attention to the stock market, and from that day forward he began cutting rates aggressively.

The effects of monetary easing showed up faster than expected: growth, which had been close to zero, rebounded.

But collateralized debt obligations (CDOs), which began to expand during this period, later became a key driver of the 2008 global financial crisis,

and in October 2008 Greenspan appeared before Congress and acknowledged his mistakes.

Ben Bernanke (2006.02.01 ~ 2014.01.31)

Ben Bernanke, a Republican at the time of his appointment, was the 14th Fed chair.

Bernanke implemented aggressive easing in response to the Great Recession,

but before that he had been a chair who pushed rates up to 5.25% on June 29, 2006, in an effort to rein in inflation.

What happened that made him reverse course after steadily hiking to fight inflation?

On September 18, 2007, following an FOMC meeting,

Bernanke cut the federal funds rate from 5.25% to 4.75%.

“I did not hear a great deal of opposition to the principle that the Federal Reserve at times should help markets function when they are in a state of panic or otherwise in serious dysfunction.”

“I did not hear much opposition to the principle that when markets are in a state of panic or severe dysfunction, the Fed should step in to help them function.”

The Fed had come to recognize the turmoil in the housing and financial markets, and it cut rates to prevent that turmoil from bringing down the broader economy.

The key here is the set of factors that led the Fed to define the situation as “panic” and to respond with rate cuts.

Home prices had already peaked at $230,400 in July 2006 and were declining, and existing home sales had started to fall after hitting an annualized peak of 5.79 million units in February 2007.

On February 26, 2007, former chair Greenspan warned of a possible recession, triggering a brief drop in the stock market,

but Bernanke quickly reassured the public that investors would be able to earn returns again in the next upswing of the economic cycle.

In early March 2007, markets rose despite weak economic data and headlines, but soon turned down again.

The housing slump was spreading into financial firms. Bear Stearns, then one of Wall Street’s five major investment banks, saw its share price plunge and was eventually acquired by JPMorgan with the Fed’s assistance.

Up to that point, the Fed was more worried about inflation than about a slowdown. (See the March 20–21 meeting.)

In September 2007, the National Association of Realtors announced that the median existing home price had fallen 1.7% year-on-year.

It was the largest drop since a 2.1% decline in November 1990. Only then did rates finally start to come down.

The Fed did not commit to any further rate cuts that day,

but as markets slid into the Great Recession in September 2008, the policy rate was slashed to 0.25% by December 2008.

In Bernanke’s tenure, rate cuts were, in effect, forced upon the Fed by circumstances.

Janet Yellen (2014.02.01 ~ 2018.01.31)

Janet Yellen, a Democrat, was the 15th Fed chair.

Throughout her term, Yellen only raised rates; she never cut them.

After a long stretch with rates pinned at 0.25%, markets hung on her every word, trying to anticipate when she would finally start hiking,

but Yellen failed to secure a second term, and unlike other chairs, she had little chance to leave a distinct mark through a major policy pivot.

Jerome Powell (2018.02.01 ~)

Jerome Powell, a Republican, is the 16th Fed chair.

He is, of course, the face we are most familiar with today.

On July 31, 2019, following a press conference,

Powell cut the policy rate from 2.5% to 2.25%.

“The outlook for the U.S. economy remains favorable, and this action is designed to support that outlook.”

“The outlook for the U.S. economy remains favorable, and this decision is intended to support that outlook.”

Powell explained that the rate cut was a response to sluggish global growth and uncertainty stemming from trade policy.

In other words, with the world struggling to grow and trade frictions mounting, he intended to use interest rates to support the labor market and safeguard U.S. growth.

Greenspan cut rates when he saw imbalances between the labor market and wages, and when growth and earnings per share were falling sharply while unemployment was rising,

and Bernanke cut when the financial crisis had arrived and he had no choice but to use aggressive easing to revive the economy.

Each responded with rate cuts under those respective conditions.

Among these episodes, the period that most closely resembles Powell’s current situation is 1995.

Back then, after rate hikes aimed at curbing inflation since 1992, concerns about a recession were mounting.

Powell has made it clear that he looks to history as a reference when making rate decisions.

“...The historical record cautions strongly against prematurely loosening policy.”

“...The historical record offers a strong warning against easing policy too early.”

He is also aiming for a Greenspan-style soft landing, using rate adjustments to offset the damage to the real economy as much as possible.

“These are the unfortunate costs of reducing inflation. But a failure to restore price stability would mean far greater pain.”

“These are the unavoidable costs of bringing inflation down. But if we fail to restore price stability, the pain will be far greater.”

To sum up,

if Powell eventually does cut rates, it will most likely be because he is worried that economic conditions are deteriorating in a serious way.

And the indicators that pushed Greenspan to worry about economic deterioration were:

economic growth, unemployment, earnings per share, and retail sales.

Recently, parts of Amazon, Qualcomm, and Meta, as well as some Apple divisions, have frozen hiring,

and startups of all sizes—including Lyft, Stripe, Gopuff, Snap, and Calm—have carried out layoffs ranging from about 10% to as much as 20% of staff.

Big Tech earnings have also come in weaker than expected.

Taking all this into account, it is not unreasonable to think that Powell’s recent hint at slowing the pace of rate hikes reflects these developments.

Three-line summary:

1. Looking at past shifts to easing since 1987, today’s environment most closely resembles 1992–1995.

2. Powell is likely drawing most heavily on former chair Greenspan’s decisions as a reference.

3. The factors that led Greenspan to cut rates were economic growth, unemployment, earnings per share, and retail sales.

Newsletter

Be the first to get news about original content, newsletters, and special events.